Much has changed in the last 25 years regarding space weather.

Technology has improved and scientists have gained insight into extreme space weather events following historic geomagnetic storms such as Halloween solar storm in October 2003 AND The Gannon event in May 2024. Looking to the future, scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) are now looking for ways to better communicate with the public about space weather events that could affect Earth. That’s why NOAA is seeking public input on how to rewrite its space weather scales.

NOAA published a request in cooperation with the National Weather Service (NWS) asking organizations and the public to share information on which revisions could help update the space weather scale. The goal is to make it easier to understand the space weather conditions that can develop and how they can affect people in space and on Earth, as well as various systems that have been affected in the past.

“The user base and the needs have changed, the skills, the science and our understanding of the science—a lot has changed. And the scales for all practical purposes haven’t changed, and they should.” Bill Murtagh, program coordinator for NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC), told Space.com in an interview.

NOAA Space Weather Scales were created in 1999 when space weather began to gain popularity with the introduction of new technology to study weather in outer space. The spacecraft were equipped with various instruments to study the solar wind and also to keep a watchful eye on the sun’s activity.

“Space weather was really starting to evolve as a science of interest in many sectors because we were starting to appreciate it as each new technology was introduced, developed, and evolved vulnerabilities to space weather came with it,” Murtagh said. .

NOAA’s space weather scales were modeled after existing scales used to categorize meteorological events here on Earth. “We had discussions here at SWPC in 1997-1998 that we should have scales, but we wanted the scales to be something that the citizens of this nation could understand,” Murtagh explained.

“Everybody understands what a Category 5 hurricane or an EF-4 tornado is, so we modeled our scales on those scales, basically, which is one to five. That’s what citizens can appreciate, with a small and five in the extreme.”

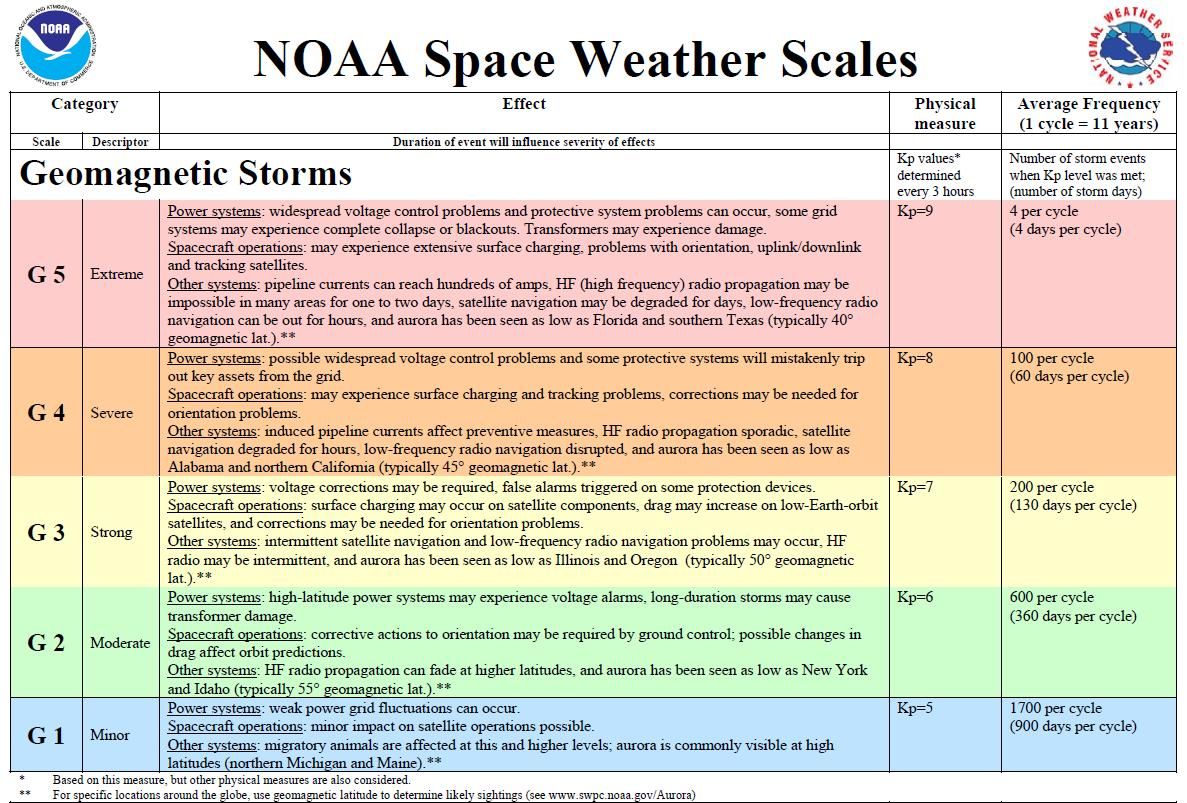

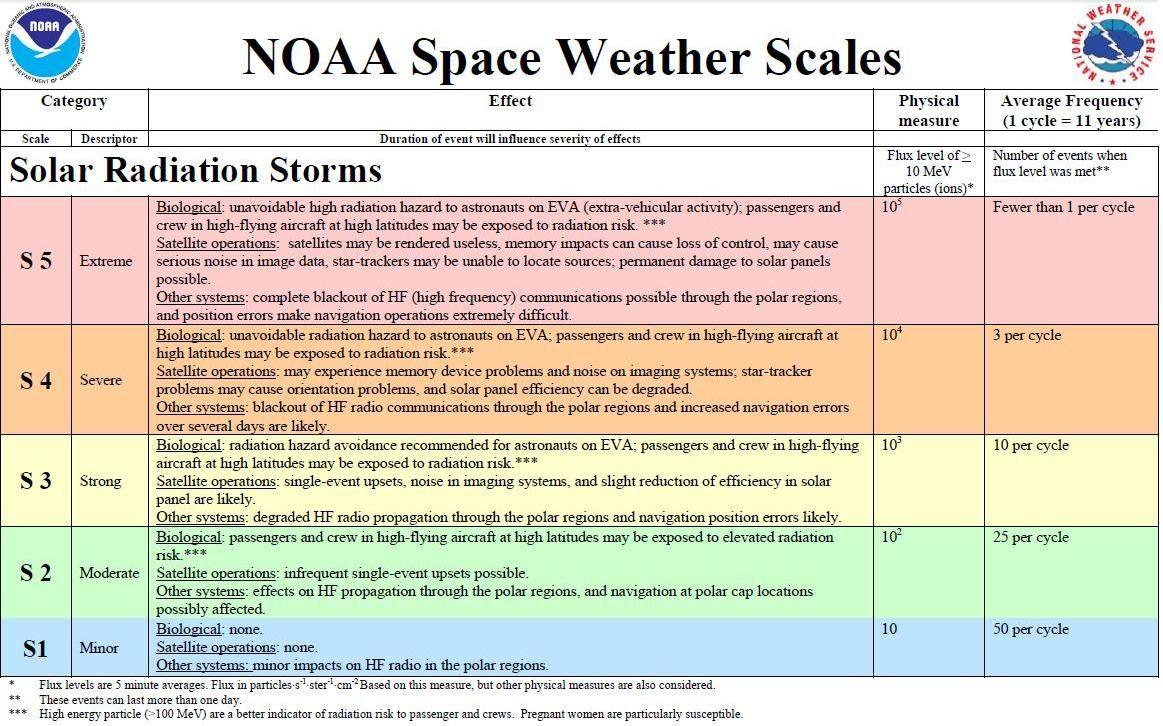

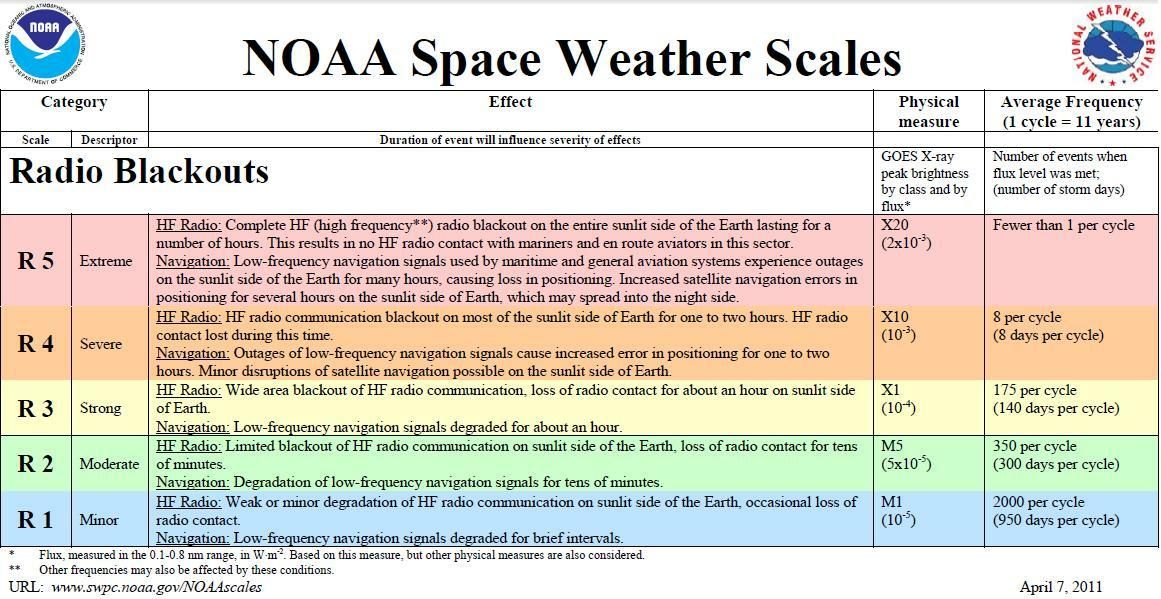

There are three different events than the scale are about explaining the different types of environmental impacts they can have and their severity. In addition, each of the scales includes details of how likely each type of event occurs on average and the type of intensity associated with each level.

For geomagnetic storms, the scale categories focus on impacts on spacecraft operations, power grids, and other ground infrastructure.

In the solar radiation categories, effects include biological effects on astronauts and passengers on board, as well as how satellites and other systems may be affected.

The third level, radio disruptions, focuses on the effects that space weather can have on high frequency (HF) radio as well as navigation systems.

Murtagh explained that the scale was based on three main groups of impacts resulting from solar flare events.

“We identified what we consider the three main areas, the three main elements from a solar flare. The first is the solar flare, the emissions, what we call the solar flare radio cutoff (R). Shortly after that, we” we put in our energetic particles, our energetic protons, and that’s our S-scale radiation storm and then the last part, the large coronal mass ejection (CME),” Murtagh said.

“It makes its way to Earth, affects the magnetic field, and then we have a geomagnetic storm, and that would be G scale.”

Since the ladders were created, their user base began to evolve, expanding from a general public eager for knowledge to various companies that became more engaged with how space weather can specifically affect the communities and clients they served.

For example, emergency response organizations such as Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) began to ask more of the SWPC if and how radio interruptions could affect satellite and cell phone communications based on the wording on the rate of radio interruptions. Other examples included concerns about the varying levels of “radiation” a solar storm might imply.

“We have the level called Solar Radiation and the S4 level called severe radiation. I have told the public that the radiation environment will increase when they are in the air to such a degree that we are going to call it a severe radiation storm , it causes a lot of concern,” Murtagh said.

Even airlines told NOAA they want to better understand what the scale means for their passengers.

“We had the major airlines here with us last year, and they all said, ‘You guys have to change this, don’t you?’ We had severe turbulence, we had severe frost, and we know what that means, but are people going to get off the plane vomiting from radiation sickness, are people going to die and so on? we’ve had to address is service,” Murtagh said.

Spacecraft operators are also interested in new scales of space weather as more and more commercial companies depend on satellites for services, said Kim Klockow McClain, senior social scientist for the National Weather Service (NWS).

“Think about all the cube constellations; those things are being used as critical infrastructure in some countries and will be what provide internet in some developing countries. We’re putting a lot in low Earth orbit in places that are so vulnerable to some of these phenomena, some of which don’t directly account for scales like neutral density,” Klockow told Space.com in an interview.

“We need to think about what decisions people are making on the ground and go beyond categorizing our risks to actually trying to communicate something about the impacts. That’s a challenge that crosses all areas of risk,” Klockow added.

NOAA is expected to finalize findings about the new space weather sensors by the end of the year, and the information will then be shared across various government agencies, including the White House, the Department of Energy, the Department of Transportation and Federal Aviation Administration. (FAA). The results will guide teams at NOAA and NWS in making decisions about what revisions should be made in the immediate and long term.

“We’ll say, option one is this, I think this is something we should do and maybe with this modification, we can do it in six months. Option two, very good idea, it will take three years and I recommend that we pursue all those kinds of discussions and I think we can make changes to the scales that are meaningful within a few months in 2025,” Murtagh said.

“I think we can make some small but significant changes at scale. We can do a lot in the short term, but there will be some significantly larger efforts down the road in the next year or so.”